Archaeological Reconnaissance in Southeastern Campeche, Mexico

Principal Investigator at ZRC SAZU

Ivan Šprajc, PhDProject Team

Aleš Marsetič, PhD, (2007, 2013, 2014, 2017, 2023, 2024), Saša Čaval, PhD, (2007), Asst. Prof. Tomaž Podobnikar, PhD, (2004, 2005)-

Duration

1 February 1996 -

Project Leader

-

Financial Source

* Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (Mexico)

* Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (USA)

* Committee for Research and Exploration, National Geographic Society (USA)

* Universidad Autónoma de Campeche (Mexico)

* ZRC SAZU (Slovenia)

* Ars longa, Travel Agency, Slovenia (Slovenia)

Candzibaantún, Main Compound; A. Baker Pedroza, A. Flores Esquivel and I. Šprajc, upon finding the site in 2005.

In twelve field seasons accomplished in the archaeologically little known central parts of the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico, i.e. in the heartland of the territory once occupied by the Maya, a number of hitherto unreported archaeological sites were recorded, including major centers with large architectural complexes, sculpted monuments and hieroglyphic inscriptions containing important data on regional political history.

Fieldwork Methodology Summary Monographs Bibliography Sponsors

FOREWORD

One of the most intriguing civilizations of the ancient world was created by the peoples nowadays known collectively as the Maya. A relatively uniform culture began to emerge in the second millennium B.C. and flourished up to the Spanish Conquest on the territory corresponding to what are now the southeastern part of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras.

The southeastern part of the Mexican federal state of Campeche, even if it lies in the very heartland of the territory once occupied by the Maya, was, until recently, very poorly known from the archaeological point of view. In the surveys accomplished in these central parts of the Yucatan peninsula since 1996, we have recorded more than 80 previously unreported archaeological sites, including major urban centers with large architectural complexes and sculpted monuments with hieroglyphic inscriptions, as well as several caves with vestiges of ritual activities.

This website presents basic cartographic information and illustrative material derived from twelve field seasons of archaeological reconnaissance, and is intended to be used as a complementary source of information, together with three monographs and other published works cited in Bibliography.

Fieldwork Methodology Summary Monographs Bibliography Sponsors

INTRODUCTION

This website presents the distribution of archaeological sites in the southeastern part of the Mexican federal state of Campeche, and the corresponding illustrative material. The information derives from nine field seasons of archaeological reconnaissance, accomplished from 1996 to 2014 and directed by Ivan Šprajc. While the field data and interpretations resulting from the first eight seasons are exhaustively presented in three monographs (Šprajc 2008; 2015; Šprajc et al. 2014) the material shown here is intended to be used as a complementary source of information. The publication of results of the 2014 season is still in preparation.

The area of our surveys is located south and north of the Mexican federal highway no. 186, which crosses the Yucatan peninsula in the east-west direction, communicating the cities of Chetumal and Escárcega. In a sparsely populated strip of land, around 30 km wide and extending south of the modern town of Xpujil along the border between Mexico and Belize, colonization started about four decades ago, and the land is alloted mostly to ejidos (rural communities enjoying usufruct rights to the land held in common); the remaining territory belongs to the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, declared as a protected area in 1989 and nowadays without permanent population.

Before our surveys started, in 1996, some of the most extensive blanks on the archaeological map of the Maya area were located precisely in these central parts of the Yucatan peninsula. While the Río Bec region, defined by its typical architectural style, was relatively well known, very few archaeological data were available for the area lying south and southwest of the former and extending between the Río Candelaria and the border between Mexico and Belize (cf. Ruz 1945: 11). Until the intensive research in the area of Calakmul began, in the early 1980s (cf. Folan 1994; Folan et al. 1995; Morales 1987; Carrasco 2000), Ruppert and Denison's monumental work (1943), resulting from four expeditions accomplished by the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1932, 1933, 1934 and 1938, was practically the only source of information on some archaeological sites in this region, but the sites they reported were – according to Ruppert himself (Ruppert and Denison 1943: 1) – only a few of the largest and best preserved ones. The information on some additional sites reported afterwards (Ruz 1945; Müller 1959; 1960) is so scanty that they cannot even be identified in the field. Indeed, only few decades ago, Adams (1981: 216) affirmed that the sites in the area, except for El Palmar (Thompson 1936), “were all found by Ruppert and his Carnegie Institution surveys of the 1930s. Although some of the most impressive Maya sites lie here, notably Calakmul, no serious work has since been done in the zone.”

As an attempt to improve the situation, the reconnaissance works started in 1996 in the southeastern extreme of the state of Campeche, and continued in 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005 and 2007. We have recorded over 80 previously unknown archaeological sites, and have also managed to rediscover most of the sites that had been reported by Ruppert and Denison (1943), but whose location was later forgotten. Our surveys have revealed not only a great density of archaeological vestiges, comparable to the one observed in other parts of Maya Lowlands, but also the presence of major centers with extensive architectural complexes, sculpted monuments and hieroglyphic inscriptions. Aside from the two monographs (Šprajc 2008; Šprajc et al. 2014), presenting exhaustively the results of the first seven field seasons, those of particular seasons have been summarized in a number of preliminary reports (Šprajc 1998; 2001; 2002; 2003; 2002-2004; 2006; 2007; Šprajc et al. 1997a; 1997b; 2005; 2009; 2010; Šprajc and Juárez 2003; Šprajc and Suárez 1998; 2003; Grube 2005; Juárez et al. 2007).

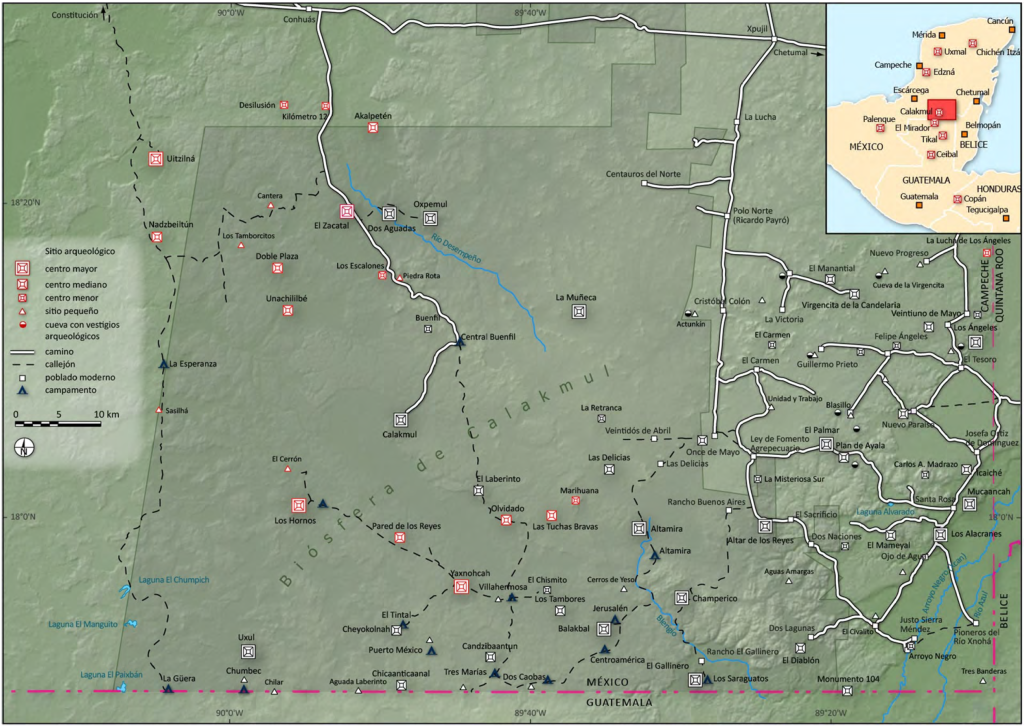

Map of the archaeological sites in the southern section of the Calakmul Biosphere (from Šprajc, 2014).

In 2013 we started reconnaissance works in the northern section of the Calakmul Biosphere, in a vast archaeologically unsurveyed area extending between the Río Bec and Chenes regions over some 3000 sq km. The site of Chactún, discovered in 2013, is one of the largest urban centers known so far in the central Maya Lowlands (Šprajc 2015). Tamchén and Lagunita, other two major urban centers, were surveyed in 2014; the results are summarized in a short article (Šprajc et al. 2015), while a monograph is being prepared for publication.

The lidar data acquired in 2016 for an area of 200 sq km around Chactún, Tamchén and Lagunita revealed a great density of archaeological remains, including residential clusters and land modifications related to water management and intensive agriculture. The analyses of abundant information collected during field surveys accomplished in this area in 2017 and 2018 field seasons are in process. Only two reports are currently available (Šprajc 2017; 2020).

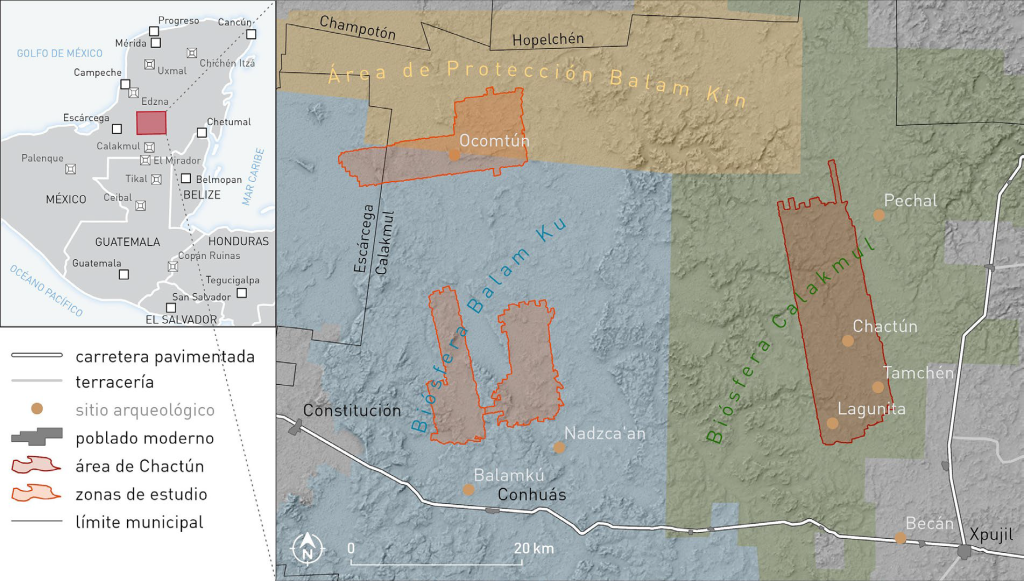

Map of the archaeological sites in the northern section of the Calakmul Biosphere (from Šprajc, 2023).

Top of page Methodology Summary Monographs Bibliography Sponsors

SUMMARY OF FIELDWORK

| 1996 field season | |

| Time span | July and August |

| Activities | surveys in the southeastern extreme of the state of Campeche (area of ejidos). |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, DRPMZA INAH), Florentino García Cruz and Héber Ojeda Mas (archaeologists, Centro INAH Campeche). |

| Sponsor | INAH. |

| 1998 field season | |

| Time span | late February to early April |

| Activities | surveys in southeastern Campeche (area of ejidos), salvage of the stelae of Los Alacranes. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, DRPMZA INAH), Vicente Suárez Aguilar (archaeologist, Centro INAH Campeche). |

| Sponsor | INAH. |

| 2001 field season | |

| Time span | early March to late May. |

| Activities | surveys in the area of ejidos and in the southeastern extreme of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), José Guadalupe Orta Bautista, Pascual Medina Meléndrez (topographers, DRPMZA INAH), Rubén Escartín Adam (geographer, DRPMZA INAH). |

| Sponsors | FAMSI, INAH. |

| 2002 field season | |

| Time span | early March to late May. |

| Activities | surveys in the area of ejidos and in the eastern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve; rescue excavations and restoration works in Mucaancah and Altar de los Reyes. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), José Guadalupe Orta Bautista, Pascual Medina Meléndrez (topographers, DRPMZA INAH), Rubén Escartín Adam (geographer, DRPMZA, INAH), Daniel Juárez Cossío (archaeologist, DEA INAH), Adrián Baker Pedroza (archaeologist, ENAH). |

| Sponsors | FAMSI, INAH. |

| 2004 field season | |

| Time span | late March to mid-June. |

| Activities | surveys in the southern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, documentation of the monuments of Oxpemul. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, ENAH), Adrián Baker Pedroza (archaeologist, ENAH), Tomaž Podobnikar (surveyor, ZRC SAZU), Raymundo González Heredia (CIHS UAC), Hubert R. Robichaux (epigrapher, UIW), Nikolai Grube (epigrapher, UB). |

| Sponsors | CRE NGS, UAC, INAH, ZRC SAZU. |

| 2005 field season | |

| Time span | March to May. |

| Activities | surveys in the southern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, ENAH), Adrián Baker Pedroza (archaeologist, ENAH), Tomaž Podobnikar (surveyor, ZRC SAZU), Nikolai Grube (epigrapher, UB), Marco Gross. |

| Sponsors | CRE NGS, ZRC SAZU. |

| 2007 field season | |

| Time span | April to June. |

| Activities | surveys in the southern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, ENAH), Saša Čaval (archaeologist, ZRC SAZU), Aleš Marsetič (surveyor, ZRC SAZU). |

| Sponsors | ZRC SAZU, Ars longa. |

| 2013 field season | |

| Time span | April to June. |

| Activities | surveys in the northern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, focused on the site of Chactún. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, UNAM), Octavio Esparza Olguín (archaeologist, UNAM), Aleš Marsetič (surveyor, ZRC SAZU). |

| Sponsors | CRE NGS, Villas, Ars longa, ZRC SAZU, Rio Bec Dreams, Martin Hobel, Ken and Julie Jones. |

| 2014 field season | |

| Time span | April to June. |

| Activities | surveys in the northern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, focused on the sites of Tamchén and Lagunita. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, UNAM), Octavio Esparza Olguín (archaeologist, UNAM), Aleš Marsetič (surveyor, ZRC SAZU), Arianna Campiani (architect, UNAM). |

| Sponsors | Ken and Julie Jones, Villas, Ars longa, Adria kombi, Rio Bec Dreams, Martin Hobel, Aleš Obreza. |

| 2017 field season | |

| Time span | March to May. |

| Activities | field surveys based on a 200-km2 lidar-scanned area in the northern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, UNAM), Octavio Esparza Olguín (archaeologist, UNAM), Luis Antonio Torres Díaz (archaeologist, UNAM), Aleš Marsetič (surveyor, ZRC SAZU). |

| Sponsors | Ken and Julie Jones, Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS), Abanka, BSL finančni inženiring d.o.o., Ars longa, Adria kombi, Rio Bec Dreams, Parka Group d.o.o., Rokus-Klett - National Geographic Slovenia, Martin Hobel, Aleš Obreza. |

| 2018 field season | |

| Time span | March to May. |

| Activities | field surveys based on a 200-km2 lidar-scanned area in the northern part of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, UNAM), Octavio Esparza Olguín (archaeologist, UNAM), Quintín Hernández Gómez (archaeologist, ENAH), Israel Chato López (archaeologist, ENAH). |

| Sponsors | Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS), Abanka, Ars longa, Rio Bec Dreams, Rokus-Klett - National Geographic Slovenia, Klemen Fedran, Martin Hobel, Aleš Obreza. |

| 2023 field season | |

| Time span | May to June |

| Activities | field surveys in a lidar-scanned area in central Campeche. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Aleš Marstetič (surveyor, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, UNAM), Octavio Esparza Olguín (archaeologist, UNAM), Quintín Hernández Gómez (archaeologist, ENAH), Vitan Vujanović (archaeologist, University of Bonn). |

| Sponsor | Ken and Julie Jones, Peter Thornquist, Leslie Martin, Rokus-Klett - National Geographic Slovenia, Adria kombi, Kreditna družba Ljubljana, Ars longa. |

| 2024 field season | |

| Time span | April to May |

| Activities | field surveys in two lidar-scanned areas in central Campeche. |

| Participants | Ivan Šprajc (archaeologist, project director, ZRC SAZU), Aleš Marstetič (surveyor, ZRC SAZU), Atasta Flores Esquivel (archaeologist, UNAM), Octavio Esparza Olguín (archaeologist, UNAM), Quintín Hernández Gómez (archaeologist, ENAH), Vitan Vujanović (archaeologist, University of Bonn). |

| Sponsor | Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS), Ken and Julie Jones, Milwaukee Audubon Society, Peter Thornquist, Leslie Martin, Adria kombi, Ars longa, Rokus-Klett. |

Top of page Fieldwork Summary Monographs Bibliography Sponsors

NOTES ON METHODOLOGY

The fieldwork methods were conditioned by environmental peculiarities of the Maya Lowlands (dense tropical vegetation) and other considerations extensively presented elsewhere (Šprajc et al. 1997b: 30-33; Šprajc 2008). While the surveys depended heavily on the data provided by local informants, large scale aerial photography was also used in the last field seasons. It should be emphasized that, in view of the circumstances discussed elsewhere (Šprajc et al. 1997b: 30ss; Harrison 1981: 261; Nalda 1989: 4, 24), a project aimed at recording all archaeological features visible on the surface would be prohibitively expensive and impossible to accomplish in a reasonable time, particularly if we consider the vast territory and its environmental characteristics, as well as the high density of archaeological remains. Major sites that can be classified as centers (Ashmore 1981: 55-56; Willey 1981: 391f) were therefore given priority in the surveys. Such a strategy should by no means be considered as reflecting an "elitist" approach, but was rather dictated by the necessity of recovering the information that is in the most imminent danger of disappearance due to the looters' interests.

The exact location of every concentration of archaeological remains was determined in the field with a portable GPS navigator. Basic characteristics of archaeological features, their extent, and peculiarities of natural environment were recorded, pertinent photographs were taken and samples of available surface material were collected. Selected major sites were mapped with a total station during the final stage of each field season. The resulting maps show both contours and structures represented in accordance with conventions used in Maya site mapping (cf. Tourtellot et al. 1993: 102).

It should be pointed out that our “sites” are rather arbitrary units. If several concentrations of archaeological remains were close together, they were often assumed to form a single site, but the proximity in space does not necessarily indicate relationship in organizational terms; and inversely, some neighboring sites recorded as separate sites may have been parts of a single territorial unit.

The classification of sites in four categories (major center, medium center, minor center and small site) is based mainly on the ranking systems previously proposed by Hammond (1975), Adams and Jones (1981; cf. Adams 1981) and Guderjan (1991). While the arguments supporting this classification are presented in detail elsewhere (Šprajc 2008), only the main characteristics of the four ranks will be summarized here.

Major centers are characterized by monumental architecture that includes ceremonial, residential and administrative buildings arranged in various groups and around several plazas. Temple pyramids over 20 m high are common at these sites, as well as ballcourts and sculpted monuments, many of them with hieroglyphic inscriptions.

Medium centers are, obviously, smaller and their architecture is less diversified, but their constructions, even if less voluminous than at major centers, as well as the presence of monuments in some cases, occasionally with hieroglyphic inscriptions, attest to their relative importance on regional level.

The distinction between medium and minor centers is somehow arbitrary, based on a rather subjective comparison of construction volumes. Some minor centers have few buildings, at least one of which can be fairly voluminous, while others are of a greater extent and have a larger number of smaller structures. It is very likely that at least some of the minor and medium centers are, in fact, outliers of larger centers in the neighborhood; such a relationship can be supposed, for example, between El Chismito and Los Tambores, Plan de Ayala and El Palmar, or between Los Ángeles Norte and Los Ángeles.

All the remaining settlements, i.e. those that do not have plazas and could not be connected to a nearby center, have been classified as small sites. In most cases they consist only of low, evidently residential mounds whose number may vary considerably. Occasionally they include pyramidal mounds, probably local lineage shrines, e.g. at El Civalito, Dos Caobas and Tres Banderas, or structures that may have been residences of local elites.

While this ranking was possible for the sites recorded from 1996 to 2014, field surveys in 2017 and 2018, based on lidar imagery of an area of 200 sq km comprising Chactún, Tamchén and Lagunita, revealed a much more complex picture. The whole area has turned out to be a thoroughly modified cultural landscape: the great density of residential clusters, agricultural terraces, wetland canals and other land modifications makes it impossible to determine "sites" as distinct and clearly delimited concentrations of archaeological vestiges. It is to be expected that the analyses of the complex information collected in the area will allow us to formulate hypotheses about the dynamics of community patterning, political geography and land use.

Top of page Fieldwork Methodology Monographs Bibliography Sponsors

SUMMARY OF RESULTS

Like Harrison's (1981: 262) survey in Quintana Roo, our method was also “by nature nonsystematic and biased in favor of larger sites,” but it can be said that our knowledge of archaeological sites in southeastern Campeche has increased notably. Following are some of the most important conclusions.

All of the archaeological sites are Maya, mostly remains of settlements consisting of structures and spaces with residential, religious, administrative, and other functions. Buildings are regularly arranged in patio groups, and clusters of groups are focused on particular groups or individual structures (Ashmore 1981: 51-53, figs. 3.5 and 3.6). Elaborate patio groups often have a major structure on the east side and thus conform to the Plaza Plan 2 architectural configuration defined for Tikal by Becker (1971; 1991). Large courtyards or plazas are present at major sites. Chultuns are commonly found within the sites and aguadas nearby. Monumental architecture and urban patterns seem to share certain characteristics with the Petén, on the one hand, and with northern Belize, on the other. The settlements are largely Classic (A.D. 250 – 900), but since a number of earlier complexes of monumental architecture were also found, it is evident that a considerable population density and high levels of social complexity had been reached as early as the Late Preclassic period (300 B.C. – A.D. 250), paralleling the developments well documented in the Mirador Basin in northern Guatemala (Hansen 1990; 1994).

In addition, some interesting caves were inspected, with archaeological features suggesting their predominantly ritual use; they are regularly placed in the vicinity of settlement remains. The region is evidently promising for further studies, which should contribute to the understanding of the relationship between the caves, settlement patterns, and the Maya world view (Thompson 1959; Bassie-Sweet 1996; Brady 1997).

Although standing architecture is rarely preserved, the size and characteristics of architectural remains at several sites suggest they were important centers in a regional political hierarchy. While it is obvious that not all of the sites ranked as major centers had the same position in political hierarchy, the nature of archaeological remains, however, allows at least some of them to be characterized as major foci of regional territorial organization. Apart from El Palmar, Balakbal, Oxpemul, Uxul and Altamira, which have long been known (Thompson 1936; Ruppert and Denison 1943), Los Alacranes, Mucaancah, El Gallinero, Champerico, Yaxnohcah and Altar de los Reyes must have been particularly important centers. Concerning their location with regard to natural environment, most of these sites can be added to the long list of Maya centers situated characteristically on the edges of large bajos or seasonally flooded swamps, apparently as a result of agricultural advantages offered by such placement (cf. Harrison 1981: 273; Folan et al. 1995: 311; Adams 1999: 39s, 154).

While little can be said at this point about the larger territorial organization in the area, the epigraphic data do contain some specific information concerning these issues. The interpretation of the texts found at several sites has revealed their toponyms, comparable to emblem glyphs, as well as some facts about the nature of their relationship with the most important Classic period centers of the central Lowlands, such as Calakmul and Tikal. A particularly remarkable monument is Altar 3 of Altar de los Reyes, with its series of emblem glyphs. The inscription is not complete and its exact meaning remains unclear, but the references to sites as distant as Palenque and Edzná (about 280 km and 200 km to the southwest and northwest, respectively) give an idea about the extent of the interaction sphere of Altar de los Reyes, or at least about the range of its familiarity with the surrounding Late Classic polities (Grube 2005).

Particularly interesting are the sites of Chactún, Tamchén and Lagunita, which are located in the northern part of the Calakmul Biosphere and were surveyed in the 2013 and 2014 field seasons. The spectacular zoomorphic portal found at Lagunita, representing open jaws of an earth monster, is a typical element of the Late Classic Río Bec architectural style, which developed in the nearby region to the south. Surprisingly, however, other characteristics of the three sites link them much more with the so-called Petén tradition in a wider surrounding area. Voluminous residential and administrative buildings arranged around large plazas, numerous temple pyramids, and monuments with inscriptions stand in a sharp contrast with the nearby Río Bec sites, where “false” pyramid towers, instead of true pyramids, are common, the architectural groups are typically smaller and with fewer structures, and stelae with inscriptions are quite rare. Moreover, the circumstances in which various monuments were located indicate that certain activities continued to take place at the three settlements even after the time of their greatest splendor. The characteristics of the sites thus shed light not only on their political role and their relations with neighboring regions in the Classic, but also on the processes in the still enigmatic period of crisis that followed and which, by A.D. 1000, resulted in a total collapse of the great majority of polities in the central and southern lowlands of the Yucatan peninsula. On the other hand, stone monuments with stuccoed designs and glyphs at Chactún, unusually deep chultuns (underground chambers intended mainly for collecting rain water) at Tamchén, and some other features that so far have not been known in Maya archaeology pose a special challenge for future research in the area.

With the purpose of exploring the hinterland of Chactún, Tamchén and Lagunita, field surveys based on lidar imagery of an area of 200 sq km have been carried out in 2017 in 2018. The analyses of the enormous amount of data obtained are still in process, and should contribute to a deeper understanding of different aspects of the development of Maya culture in this part of central lowlands.

Top of page Fieldwork Methodology Summary Bibliography Sponsors

MONOGRAPHS

Ivan Šprajc, ed., "Exploraciones arqueológicas en Chactún, Campeche, México". Prostor, kraj, čas 7. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, 2015.

Ivan Šprajc, Atasta Flores Esquivel, Saša Čaval, and María Isabel García López, "Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste de Campeche, México: Temporada 2007". Prostor, kraj, čas 4. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, 2014.

Ivan Šprajc, ed., Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche: 1996-2005. BAR International Series 1742 (Paris Monographs in American Archaeology 19, Series Editor: Eric Taladoire), Oxford: Archaeopress, 2008 (ISBN 978 1 4073 0184 6). Order at: Archaeopress, UK.

Top of page Fieldwork Methodology Summary Monographs Sponsors

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Richard E. W., 1981. Settlement patterns of the central Yucatan and southern Campeche regions. In: Wendy Ashmore, ed., Lowland Maya settlement patterns, Albuquerque: School of American Research – University of New Mexico Press, 211-257.

Adams, Richard E. W., 1999. Río Azul: An ancient Maya city. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Adams, R. E. W., and Richard C. Jones, 1981. Spatial patterns and regional growth among Classic Maya cities. American Antiquity 46 (2): 301-322.

Ashmore, Wendy, 1981. Some issues of method and theory in Lowland Maya settlement archaeology. In: Wendy Ashmore, ed., Lowland Maya settlement patterns, Albuquerque: School of American Research – University of New Mexico Press, 37-69.

Bassie-Sweet, Karen, 1996. At the edge of the world: Caves and Late Classic Maya world view. Norman – London: University of Oklahoma Press.

Becker, Marshall Joseph, 1971. “The identification of a second plaza plan at Tikal, Guatemala and its implications for ancient Maya social complexity” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania). Ann Arbor: University Microfilms.

Becker, Marshall Joseph, 1991. Plaza plans at Tikal, Guatemala, and at other Lowland Maya sites: evidence for patterns of culture change. Cuadernos de Arquitectura Mesoamericana núm. 14: 11-26.

Brady, James E., 1997. Settlement configuration and cosmology: the role of caves at Dos Pilas. American Anthropologist 99 (3): 602-618.

Carrasco Vargas, Ramón, 2000. El cuchcabal de la Cabeza de Serpiente. Arqueología Mexicana VII, No. 42: 12-21.

Folan, William J., 1994. Calakmul, Campeche, México: una megalópolis maya en el Petén del norte. In: William J. Folan, coord., Campeche maya colonial, Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, 55-83.

Folan, William J., Joyce Marcus, Sophia Pincemin, María del Rosario Domínguez Carrasco, Laraine Fletcher, and Abel Morales López, 1995. Calakmul: new data from an ancient Maya capital in Campeche, Mexico. Latin American Antiquity 6 (4): 310-334.

Grube, Nikolai, 2005. Toponyms, emblem glyphs, and the political geography of southern Campeche. Anthropological Notebooks 11 (special issue: Ivan Šprajc, ed., Contributions to Maya archaeology): 87-100. Ljubljana: Slovene Anthropological Society.

Guderjan, Thomas H., 1991. Aspects of Maya settlement in the Río Bravo area. In: Thomas H. Guderjan, ed., Maya settlement in northwestern Belize: The 1988 and 1990 seasons of the Río Bravo Archaeological Project, San Antonio: Maya Research Program – Culver City: Labyrinthos, 103-110.

Hammond, Norman, 1975. Maya settlement hierarchy in northern Belize. Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility 27: 40-55.

Hansen, Richard D., 1990. Excavations in the Tigre Complex, El Mirador, Petén, Guatemala: El Mirador Series, Part 3. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation No. 62, Provo: Brigham Young University.

Hansen, Richard D., 1994. Investigaciones arqueológicas en el norte del Petén, Guatemala: una mirada diacrónica de los orígenes mayas. In: William J. Folan, coord., Campeche maya colonial, Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, 14-54.

Harrison, Peter D., 1981. Some aspects of preconquest settlement in southern Quintana Roo, Mexico. In: Wendy Ashmore, ed., Lowland Maya settlement patterns, Albuquerque: School of American Research - University of New Mexico Press, 259-286.

Juárez, Daniel, Ivan Šprajc, and Adrián Baker, 2007. Mucaancah en la perspectiva del Proyecto Sudeste de Campeche, México. In: Alejandro Martínez Muriel, Alberto López Wario, Óscar J. Polaco, and Felisa J. Aguilar, coords., Anales de Arqueología 2005, México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 216-221.

Morales López, Abel, 1987. Arqueología de salvamento en la nueva carretera a Calakmul, municipio de Champotón, Campeche. Información 12: 75-109. Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche.

Müller, Florencia, 1959. Atlas arqueológico de la República Mexicana: Quintana Roo, México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Müller, Florencia, 1960. Atlas arqueológico de la República Mexicana 2: Campeche, México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Nalda, Enrique, 1989. Reflexiones sobre el patrón de asentamiento prehispánico en el sur de Quintana Roo. Boletín de la Escuela de Ciencias Antropológicas de la Universidad de Yucatán 16, núm. 97: 3-27.

Ruppert, Karl, y John H. Denison Jr., 1943. Archaeological reconnaissance in Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Peten. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 543, Washington.

Ruz Lhuillier, Alberto, 1945. Campeche en la arqueología maya. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (Acta Anthropologica I: 2-3).

Šprajc, Ivan, 1998. Stelae from Los Alacranes salvaged. Mexicon 20 (6): 115.

Šprajc, Ivan, 2001. “Archaeological reconnaissance in southeastern Campeche, Mexico: 2001 field season report; with an appendix by Nikolai Grube”. Report to: Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies.

Šprajc, Ivan, 2002. “Archaeological reconnaissance in southeastern Campeche, Mexico: 2002 field season report; with appendices by Daniel Juárez Cossío and Adrián Baker Pedroza, and Nikolai Grube”. Report to: Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies.

Šprajc, Ivan, 2003. Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste de Campeche: temporada de 2002. En: Los Investigadores de la Cultura Maya 11, tomo I: 86-102. Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche.

Šprajc, Ivan, 2002-2004. Maya sites and monuments in SE Campeche, Mexico. Journal of Field Archaeology 29 (3-4): 385-407.

Šprajc, Ivan, 2006. Nuevos descubrimientos arqueológicos en el sur del estado de Campeche. In: Los Investigadores de la Cultura Maya 14, tomo I: 155-168. Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche.

Šprajc, Ivan, 2007. Exploraciones recientes en el sureste de Campeche. Arqueología Mexicana XV, No. 86: 74-80.

Šprajc, Ivan, ed., 2008. Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche: 1996-2005. BAR International Series 1742 (Paris Monographs in American Archaeology 19, Series Editor: Eric Taladoire), Oxford: Archaeopress.

Šprajc, Ivan, ed., 2015. "Exploraciones arqueológicas en Chactún, Campeche, México". Prostor, kraj, čas 7. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC.

Šprajc, Ivan, ed., 2017. Paisaje arqueológico y dinámica cultural en el área de Chactún, Campeche (2016-2018): Informe de la temporada 2017. México: Instituto Nacional de Antroplogía e Historia, Archivo Técnico.

Šprajc, Ivan, ed., 2020. Paisaje arqueológico y dinámica cultural en el área de Chactún, Campeche (2016-2018): Informe de la temporada 2018. México: Instituto Nacional de Antroplogía e Historia, Archivo Técnico.

Šprajc, Ivan, ed., 2023. Ampliando el panorama arqueológico de las tierras bajas mayas centrales: Informe de la temporada 2023. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Archivo Técnico.

Šprajc, Ivan, ed., 2025. Ampliando el panorama arqueológico de las tierras bajas mayas centrales: Informe de la temporada 2024. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Archivo Técnico.

Šprajc, Ivan, Octavio Esparza Olguín, Arianna Campiani, Atasta Flores Esquivel, Aleš Marsetič, and Joseph W. Ball, 2015. Chactún, Tamchén y Lagunita: primeras incursiones arqueológicas a una región ignota. Arqueología Mexicana XXIII (136): 20-25.

Šprajc, Ivan, Atasta Flores Esquivel, Saša Čaval, María Isabel García López, and Aleš Marsetič, 2010. Archaeological reconnaissance in southeastern Campeche, Mexico: summary of the 2007 field season. Mexicon 32 (6): 148-154.

Šprajc, Ivan, Atasta Flores Esquivel, Saša Čaval, and María Isabel García López, 2014. "Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste de Campeche, México: Temporada 2007". Prostor, kraj, čas 4. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC.

Šprajc, Ivan, William J. Folan, and Raymundo González Heredia, 2005. Las ruinas de Oxpemul, Campeche: su redescubrimiento después de 70 años en el olvido (1934-2004). In: Los Investigadores de la Cultura Maya 13, tomo I: 20-27. Campeche: Universidad Autónoma de Campeche.

Šprajc, Ivan, Florentino García Cruz, and Héber Ojeda Mas, 1997a. Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste de Campeche, México: informe preliminar. Mexicon 19 (1): 5-12.

Šprajc, Ivan, Florentino García Cruz, and Héber Ojeda Mas, 1997b. Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste de Campeche. Arqueología: Revista de la Coordinación Nacional de Arqueología del INAH, segunda época, no. 18: 29-49.

Šprajc, Ivan, and Daniel Juárez Cossío, 2003. Altar de los Reyes, sitio del sureste de Campeche. Arqueología Mexicana X, núm. 59: 5.

Šprajc, Ivan, and Vicente Suárez Aguilar, 1998. Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche, México: temporada 1998. Mexicon 20 (5): 104-109.

Šprajc, Ivan, and Vicente Suárez Aguilar, 2003. Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche, México: temporada 1998. In: Cuarto Congreso Internacional de Mayistas: Memoria (2 al 8 de agosto de 1998), México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, Centro de Estudios Mayas, 492-505.

Thompson, J. E., 1936. Exploration in Campeche and Quitana [sic!] Roo and excavations at San Jose, British Honduras. Carnegie Institution of Washington Year Book No. 35: 125-128.

Thompson, J. Eric S., 1959. The role of caves in Maya culture. Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Völkerkunde in Hamburg 25: 122-129.

Tourtellot III, Gair, Amanda Clarke, and Norman Hammond, 1993. Mapping La Milpa: a Maya city in northwestern Belize. Antiquity 67 (254): 96-108.

Top of page Fieldwork Methodology Summary Monographs Bibliography

SPONSORS

| NGS | Committee for Research and Exploration, National Geographic Society, U.S.A. | 2004, 2005, 2013 |

| FAMSI | Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, U.S.A. | 2001, 2002 |

| INAH | Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico. | 1996, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004 |

| UAC | Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, Mexico. | 2004 |

| ZRC SAZU | Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Slovenia. | 2004, 2005, 2007, 2013 |

| AL | Ars longa, Travel Agency, Slovenia. | 2007, 2013, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2023, 2024 |

| BMI | BMI d.o.o., consulting, constructions, planning and finance, Slovenia. | 2007 |

| Villas | Villas, Austria | 2013, 2014 |

| Rio Bec Dreams | Rio Bec Dreams, Mexico | 2013, 2014, 2017, 2018 |

| KJJ CF | Ken and Julie Jones - KJJ Charitable Foundation, USA. | 2013, 2014, 2017, 2023, 2024 |

| Adria Kombi | Adria Kombi, Slovenia | 2014, 2017, 2023, 2024 |

| ARIS | Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, Slovenia | 2017, 2018, 2024 |

| Abanka | Abanka, Slovenia | 2017, 2018 |

| Rokus-Klett | Rokus-Klett – National Geographic Slovenia, Slovenia | 2017, 2018, 2023, 2024 |

| Parka Group | Parka Group d.o.o., Slovenia | 2017 |

| BSL | BSL Finančni inženiring d.o.o., Slovenia | 2017 |

| KDL | Kreditna družba Ljubljana, Slovenia | 2023 |

| MAS | Milwaukee Audubon Society, U.S.A. | 2023, 2024 |

| Private donators | Martin Hobel, Austria (2013, 2014, 2017, 2018). Metod Zavodnik, Slovenia (2013). Aleš Obreza, Slovenia (2014, 2017, 2018). GKTI Izobraževanje, Slovenia (2017). Zavarovalnica Triglav, Slovenia (2017). Klemen Fedran, Slovenia (2018). Peter Thornquist, U.S.A. (2023, 2024). Leslie Martin, U.S.A. (2023, 2024). | 2013, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2023 |

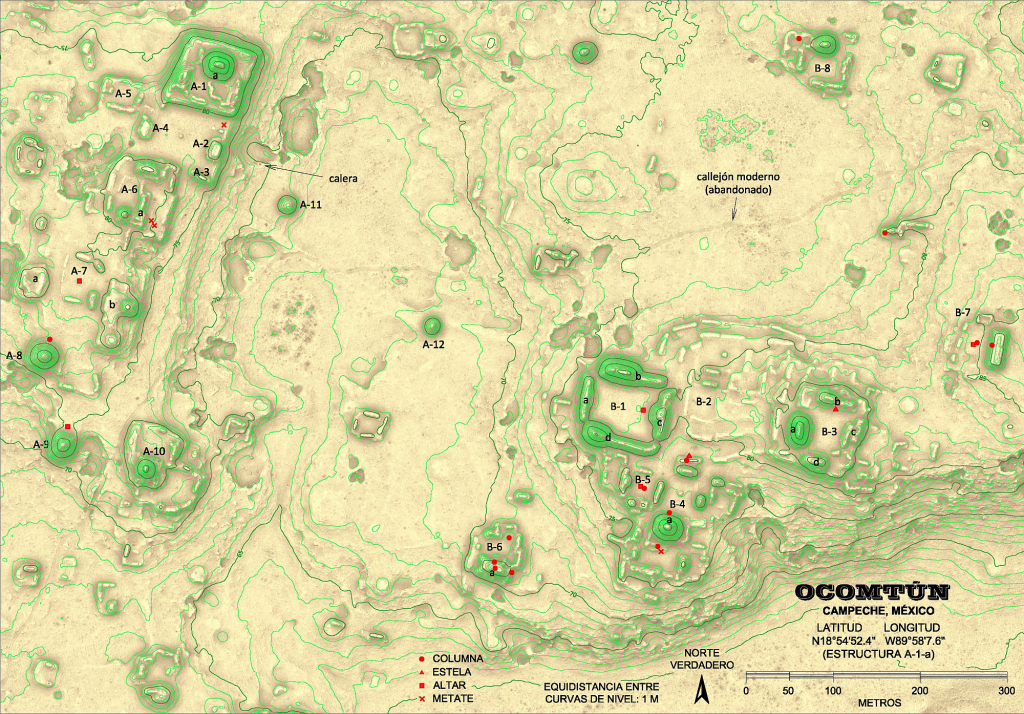

Ocomtún, plan of the monumental nucleus (from Šprajc, 2023).